Koki Tanaka : Faraway, So Close(e-flux)

19 April – 31 May 2021

Week#1 April 19-25, 2021

Bruce and Noman Yonemoto, Framed, 1989

URL= https://www.e-flux.com/video/

Week#2 April 26- May 2, 2021

Yoi Kawakubo, Waiting for Diogenes, 2020

Week#3 May 3-9, 2021

Zhu Xiaowen, Oriental Silk, 2015

Week#4 May 10- 16, 2021

Darcy Lange, Studies of Teaching in Four Oxfordshire Schools, 1977

Week#5 May 17-23, 2021

Back and Forth Collective (Mei Homma, Natsumi Sakamoto, Asako Taki), Jennifer Clarke, Fionn Duffy and Sarah McWhinney, Speculative Fiction: Practicing Collectively, 2020

Week#6 May 24-30, 2021

Yuki Iiyama, Old Long Stay, 2020

How human can our lives really be when infection prevention measures do not allow us to even mourn the deaths of our loved ones? I, you, we each have only one life to live. One birth, one death.

Ironically enough, the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic has proved that the world is a single, globally connected community. Infiltrating one person after another, the virus reveals what it means to be human as it circles the globe. Humans are beings that touch each other. We make friends, make love, occasionally make enemies, and have built our societies, our communities, and our families through contact-based communication.

At the same time, the virus divides those societies that humanity has built up and exposes the problems within them. Over the past year we have fallen into despair while clinging on to hope. Although we have seen the utopias of mutual aid and care that can arise out of disasters, in some cases, widespread anxiety brought on by the uncertainty about where things are headed has also been turned into hatred toward others.

Compared to the cities around the world that are in lockdown, Kyoto, where I live, has had only a few cases of Covid-19, and the atmosphere is still fairly relaxed. But, we constantly wash our hands and spray them with alcohol (which leaves my skin raw and chapped all the time). We wipe down our shopping with disinfectant sheets. We have delivery people leave packages outside our door. Maybe you feel the same way, but I’m afraid of infecting my family—especially my newborn child.

All kinds of concepts are getting thrown about now—from tele-working to social distancing to the new normal. Spread by epidemiologists and governments, these concepts can at times flatten the view of the world.

Social distancing, for example, promotes a view that applies a single standard to the diversity of our world. If we think about prevention measures individually, taking into account the circumstances of each person, it is true that everyone should have their own distance. But that kind of case-by-case judgment complicates our understanding of the world. So, we end up turning to an easy standard.

Daily reports on the numbers of new cases and deaths further accelerate the world’s flattening. These numbers in their tens and hundreds of thousands make us forget that each one of the counted—recognizable only as abstract data—represents its own distinct life.

The world has been overrun by the abstractions of concepts and numbers while our irreplaceable, individual lives go neglected. Yet, care for the other can make an abstract world more concrete.

I’m reading ethnographer Annemarie Mol’s book The Logic of Care: Health and the Problem of Patient Choice (2008) at the moment. Mol uses the term “logic of choice” to describe the thinking behind the contemporary model of medical practice in which, rather than having the doctor unilaterally decide the care, the patient is expected to autonomously choose their own care after considering all the information and available options. But with some chronic diseases like diabetes—which Mol’s research focuses on—a complete cure or even a single course of treatment is almost impossible. Thus, the patient can only learn to manage their condition. Here, Mol discovers a logic of care at work. Where the logic of choice places the burden of decision on an autonomous patient, the logic of care privileges a collective approach, comprising not just doctors, nurses, or care workers, but also the family who live with the patient. And instead of choosing a uniform or generalized method, the emphasis is on providing individually responsive care and daily adjustments (what Mol calls “doctoring”) based on the concrete circumstances of the patient.

One thing I have come to realize from raising a child is that, no matter what style I set out to follow, childcare is always done on the basis of this child in front of me. Care is always about the individual patient; it is always concrete.

I view the relationship between the logic of choice and the logic of care that Mol discusses in her book in parallel with the relationship between an abstracted world and individual, concrete life during the pandemic. The autonomous individual is the premise for the logic of choice, but the truth is there is no such thing as an autonomous being. The pandemic has shown us just how fast our societies can collapse without our networks of interdependencies. The patient’s care network that Mol describes in the logic of care is not just about medical treatment. For us who live a life of collective interdependence, it is also about society itself.

The six videos presented in this program all either examine concrete life or show us how to recover it. What we need most right now is not the spread of more abstractions about the pandemic, but to look attentively at your concrete life, and then the concrete life of another.

Kyoto

January 23, 2021

—Koki Tanaka; translated from the Japanese by Andrew Maerkle

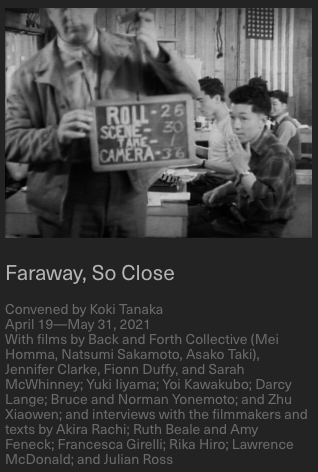

Faraway, So Close

is a program convened by Koki Tanaka as the sixth cycle of Artist Cinemas, a long-term, online series of film programs curated by artists for e-flux Video & Film. Faraway, So Close! will run for six weeks from April 19 through May 31, 2021 screening a new film each week accompanied by an interview with the filmmakers(s) conducted by invited guests

With films by

Back and Forth Collective (Mei Homma, Natsumi Sakamoto, Asako Taki), Jennifer Clarke, Fionn Duffy, and Sarah McWhinney; Yuki Iiyama; Yoi Kawakubo; Darcy Lange; Bruce and Norman Yonemoto; and Zhu Xiaowen; and interviews with the filmmakers and texts by Akira Rachi; Ruth Beale and Amy Feneck; Francesca Girelli; Rika Hiro; Lawrence McDonald; and Julian Ross